There are fourteen independent nations in the world today that used to be Soviet states, and many more that were Soviet clients.

If we focus on continental Europe, there are six countries that can be counted among the former and even more than can be counted among the latter.

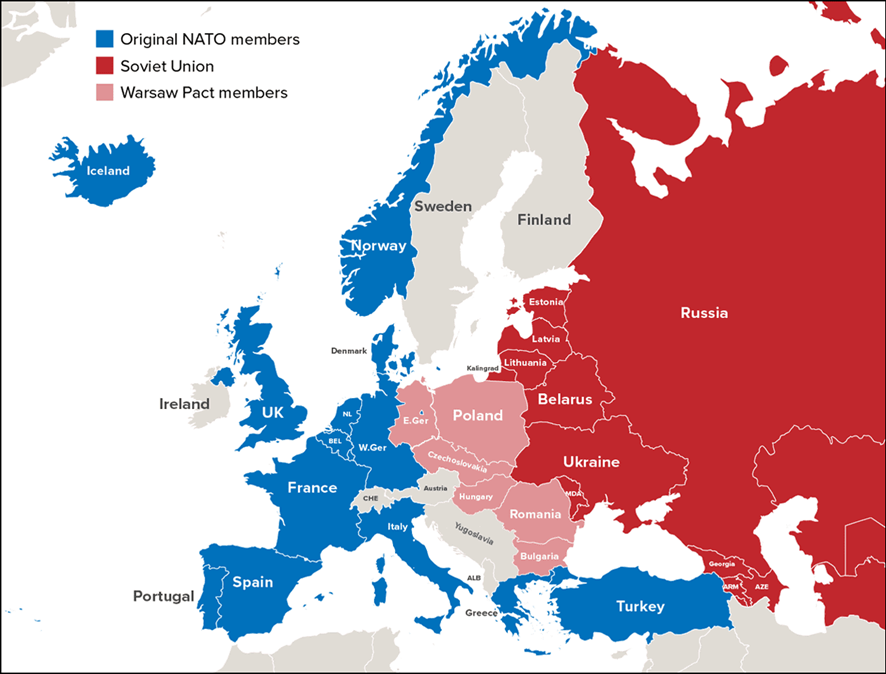

This map of 1990 Europe from CNBC illustrates the geography of Cold War Europe succinctly:

Compare it to this map of Europe in 2022, from the same article:

I thought a quick geographical refresher would be helpful before getting into today’s head-scratcher: a guest column in Saturday’s Berlingske Tidende from Marlene Wind, a Danish poli-sci professor and adviser to the EU’s Foreign Minister.

She believes “it is important to be prepared–also mentally–for what kind of discussions we (Europeans) will have to have very soon” about Europe’s role in the world.

She makes the obvious point that Europe’s going to have to be very involved with the “clean-up, reconstruction, and housing of several of the new countries that have been affected by the war,” then waves that off as “the ‘easy’ more practical part” and says it’s the architecture of the new Europe that’s going to be more difficult:

Because in the future, how will the EU be able to function with many more countries, while at the same time the community must be stronger and a more active international player? My expectation is that, whether we like it or not, we will have to have the debate on treaty changes. Changes that can ensure that more member states do not reduce the EU’s effectiveness and dynamism.

If in the future we do not embrace more countries that want Europe and our values, Putin is ready.

This is Cold War thinking. It sees Europe as a zero-sum game in which either you’re with us or you’re with Ivan, at least in the eastern European corridor comprising both sides of the former Iron Curtain.

The theme of Wind’s column is a term she says first came into use at the annual Security Policy Conference in Munich back in 2020: westlessness. It is a term, she says,

that covers the Western world’s internal division, identity crisis and existential crisis, as well as the tendency in the rest of the world to move away from the West.

She seems to credit Vladimir Putin for the growth of westlessness:

So when the Munich conference in 2020 suddenly talked about “westlessness,” it perhaps best showed how Putin had actually succeeded in making the West doubt its own values. A good example was when Donald Trump seriously considered withdrawing the US from NATO in 2018, and when Macron called NATO brain dead in 2019.

She’s claiming that Putin turned the west against itself and her two examples are (1) Trump’s skepticism about Europe’s willingness to defend itself and (2) Macron’s having responded to Trump’s skepticism by urging Europe to take its own defense more seriously.

In other words, two very different men with very different interests were both acknowledging the Russian threat to Europe and the need for Europe to man up and defend itself more aggressively, but Wind—the professor of political science and adviser to the foreign minister of the EU—says that just proves how Putin has turned the west against itself.

Huh?

Putin’s war in Ukraine has partially turned this on its head, although there is still a right and left wing in several European countries who believe that the war in Ukraine is the fault of the West and not Russia, and that peace and arms support are opposites of each other. In addition, no one really knows what the United States will do after the next presidential election or four years from now. However, something right now suggests that more people understand the need for more unity and less naïvete, although we also have to recognize that it is far from everywhere that the Russian disinformation campaign has failed.

Outside of Europe, in Africa, in India, in China, Belarus and Iran, the Russians’ story has made it through clean. There is therefore an enormous amount of work to be done for Europe, not just in relation to how we communicate with the outside world. But also about how the EU itself should be reformed, so that we appear and become more active and trustworthy.

Wind then tears into Hungary’s Viktor Orbán for sending his foreign minister on “sleazy courtesy visits” to Russia, Belarus, and Iran, “while he eagerly obstructs the EU’s common foreign policy,” then jumps right to her conclusion:

If “westlessness” was in fact an idea that Putin himself planted and made the West believe in, we must hope that the new buzzword “zeitenwende” (change of era) leads to real change when world leaders meet for another one of their many public meetings over the weekend.

So Eurocratic: our ideas are failing—quick, deploy a new word!

Let’s backtrack a little. Not long after telling readers that Putin was standing by licking his lips in anticipation of what would happen if Europe didn’t “embrace more countries that want Europe and our values,” Wind offered the following as evidence:

Rising populism and support for Trump, Orbán, and Le Pen showed, (Putin) believed, that liberalism was no longer attractive. The fact that over the past 20 years Putin himself has massively sought to influence the same entropy through massive disinformation campaigns and sponsorships for the West’s right-wing nationalists, of course, does not make his points any less interesting.

(I translated Wind’s use of opløsningstendensen, which literally means “the tendency to break up,” as entropy.)

If you read the 2019 Putin interview to which Wind is referring, you’ll get a very different sense of what Putin was saying (my emphases):

What is happening in the West? What is the reason for the Trump phenomenon, as you said, in the United States? What is happening in Europe as well? The ruling elites have broken away from the people. The obvious problem is the gap between the interests of the elites and the overwhelming majority of the people.

Of course, we must always bear this in mind. One of the things we must do in Russia is never to forget that the purpose of the operation and existence of any government is to create a stable, normal, safe, and predictable life for the people and to work towards a better future.

There is also the so-called liberal idea, which has outlived its purpose. Our Western partners have admitted that some elements of the liberal idea, such as multiculturalism, are no longer tenable.

When the migration problem came to a head, many people admitted that the policy of multiculturalism is not effective and that the interests of the core population should be considered. Although those who have run into difficulties because of political problems in their home countries need our assistance as well. That is great, but what about the interests of their own population when the number of migrants heading to Western Europe is not just a handful of people but thousands or hundreds of thousands?

That’s not the only part of the interview in which Putin offers thoughts on how and why “liberalism” per se is dead or dying, or in any case doomed. Nor are immigration and multiculturalism the only examples he offers of liberalism’s failures.

What’s interesting, however, is what Putin, his interviewer, and Wind seem to mean by liberalism.

Putin seems to be talking about globalist leftism: his critiques are not of democracy or political pluralism, but of the projects espoused by the globalist left—the people and organizations I usually refer to as the GLOB. Open borders, multiculturalism, secularism, technocracy, and so on.

His interviewers (Lionel Barber and Henry Foy of the Financial Times) may or may not have understood that, but neither did they press for clarification.

Wind, on the other hand, seems to be speaking of political pluralism generally, and to be conflating westerners who believe very strongly in classical liberalism—popularly referred to these days as conservatism—with the despotism she attributes to Putin.

There’s no difference to Marlene Wind between globalist leftism and western democracy. As far as she’s concerned, they’re the same thing. To oppose one is to oppose the other.

It’s hard to analogize perfectly, but let me give it a shot. Putin says rabid dogs are bad for people and therefore need to be rounded up and put to death. Wind interprets this to mean that Putin wants to all dogs killed, and that anyone in the west who’s working against rabies is actively seeking to kill all dogs—possibly because of Putin’s propaganda on the topic.

Now, it may be true that Putin is merely being coy and secretly does want to kill all dogs, but even if that were the case it wouldn’t mean that rabies was good or that rabid dogs weren’t a genuine public health threat.

Let’s be clear about what Wind is doing: she’s equating the failures of global leftism across the west with the ascendance of despotism. She’s equating criticisms of global leftism as support for despotism. Either you’re all-in on open borders, climate hysteria, gender insanity, and all the rest, or you’re Putin’s lackey.

Glenn Reynolds had an interesting Substack approaching all this from a different angle just yesterday: “Thoughts on our ruling class monoculture.” It’s worth a read, but it also boils down to a meme he includes:

Reynolds uses that meme to reinforce a citation from a man I frequently cite myself, G.K Chesteron: “When men choose not to believe in God, they do not thereafter believe in nothing, they then become capable of believing in anything.”

The GLOB—the monocultural elites—the machine, the cathedral, the anointed, whatever you want to call them—they don’t think of themselves as representing one side of a political divide within a broader political philosophy. They think of themselves as the broader philosophy itself. You’re with them, or you’re with Putin. You share (and support!) their positions on everything, or you’re anti-democratic.

Joe Biden has made this point explicitly on many occasions: he and his supporters represent not just the leftish side of American politics, but American democracy itself. His opponents don’t just have a different view of democracy: they’re enemies of democracy, a clear and present danger to the American republic.

Strands of the same thought can be seen all across western Europe right now—as can a popular reaction to that kind of thinking.

If Marlene Wind genuinely believes that Europe needs to be a more vigorous champion of political pluralism lest Vladimir Putin eat our geopolitical lunch in the years ahead, then she ought to be calling for more elasticity in what the ruling class considers legitimate governance.

If, on the other hand, she and her friends and colleagues in Brussels are going to get the vapors every time European voters elect someone of religious faith, or someone who supports their right to have their own culture, or someone who believes his or her paramount responsibility is to the welfare of the citizens of his or her own country, then the European project is dead in the water.

Woody Allen famously said he wouldn’t want to be a member of any club that would take him as a member. It’s funny and we all understand the point being made about personal insecurity and self-loathing—but I doubt many nations want to be a member of any union that disapproves of them.

“I love you, now change” doesn’t work in personal relationships and it’s not going to work in 21st century Europe.