Very few people outside of Denmark have seen or are even aware of the Danish miniseries Matador, which aired in Denmark over four seasons from 1978 to 1981.

The series chronicles life in the fictional town of Korsbæk through 24 episodes covering the bumpy years from 1929 through 1947—from the Depression through the occupation of the Second World War.

With absolutely no statistical data to back me up I’d say that from the standpoint of today it’s the most popular thing ever to have appeared on Danish television. I even heard an enthusiastic Matador partisan on the radio gleefully quoting from a Politiken journalist who called it not just the best Danish series ever, but possibly the best series ever produced—period.

The proper extent of superlatives aside, its characters have certainly become mythic figures, a veritable taxonomy of Danish archetypes, and their catchphrases can still be heard being tossed around on school playgrounds and in business boardrooms. Even in political speeches.

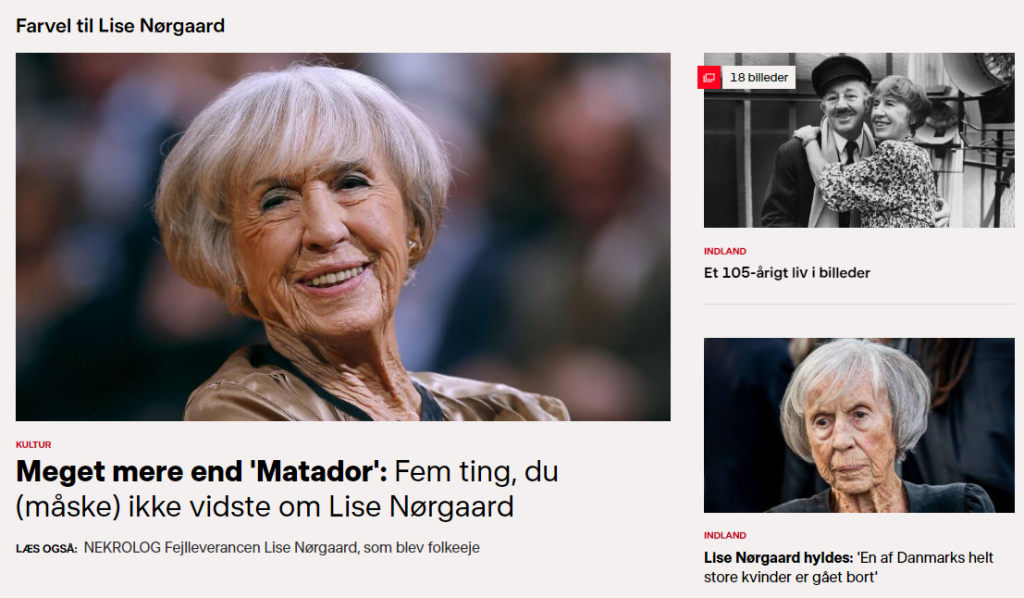

The creator of the series, its auteur, was one Lise Nørgaard, who was until Sunday one of Denmark’s living national treasures.

She’s still a national treasure but on Sunday she died at the ripe old age of 105.

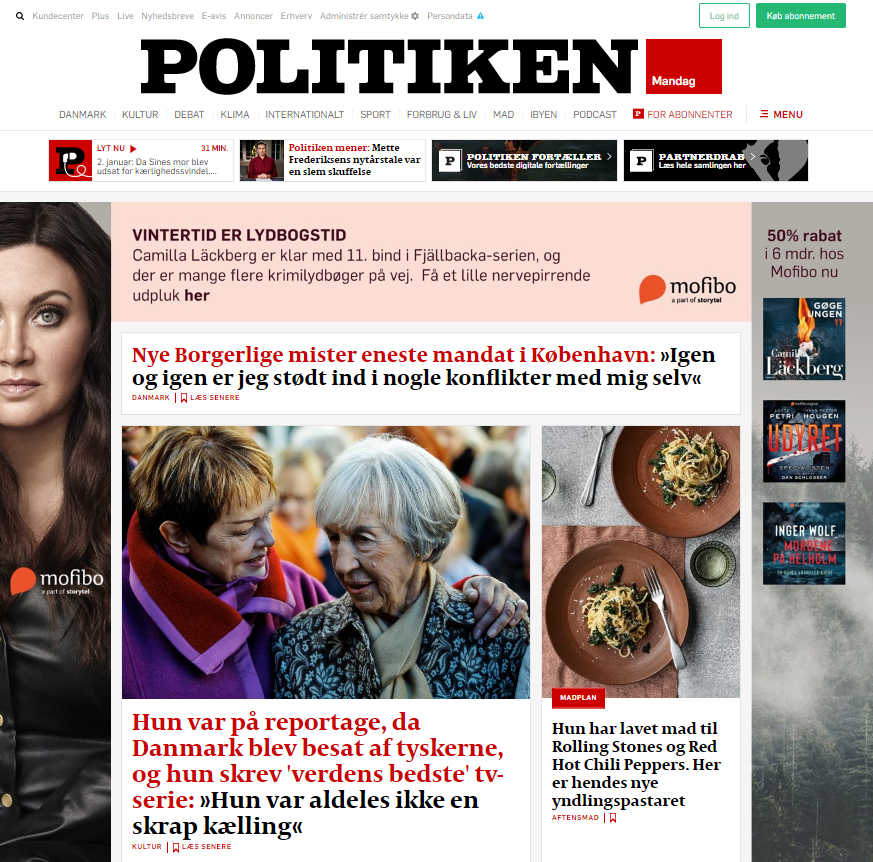

Her death knocked every other story clear off the front pages Monday morning.

DR:

Berlingske:

Politiken:

Jyllands-Posten:

…and so on.

When news of her death broke, the breaking news alerts shook my phone like it was having an epileptic fit. The screencaps above were taken later in the day, when things had cooled down, but in the morning they were sizzling on the screen, highlighted in bright red or yellow, some of them even with animated tickers announcing her death over and over and over again.

(Pope Benedict’s passing was also noted, but with what might charitably be called quiet dignity.)

Lise Nørgaard had a long and storied life, as they say, and Matador was just one small part of it, but there’s no question it’s the part she’ll be remembered for.

The English language version of Wikipedia sums up its significance:

The series has become part of the modern self-understanding of Danes, partly because of its successful mix of melodrama and a distinct warm Danish humour in the depiction of characters, which were portrayed by a wide range of the most popular Danish actors at the time; but also not least because of its accurate portrayal of a turbulent Denmark from around the start of the Great Depression and through Nazi Germany’s occupation of Denmark in World War II.

The accurate portrayal of historical events is surely part of the draw, but there’ve been plenty of historical dramas on Danish film and television exploring that pivotal era in Denmark, many of them with even more historical accuracy, and none of them has had anything close to the staying power of Matador.

It’s the characters, stupid.

If you’re a literary sort, you might think of Matador as a Danish comédie humaine: a series of intertwining stories drawing together characters from every walk of life: from pig farmers, baggage handlers, and servants to bankers, baronesses, and the idle rich. In the first episode they’re almost clichés: here’s the banking scion Varnæs lighting up a cigar while his anxious high-born wife frets about the smell; here are the earthy servant girls swapping wisecracks; here’s the snooty manager of the upscale clothing boutique tending to the fine ladies of the town with obsequious servility; and here we see the pig farmer enjoying a beer with the radical communist railyard worker at the local pub—while the wily bartender sneaks a smooch with the servant girl whose outing with the bankers’ children just happened to bring her by.

Very quickly, however, these cartoonish caricatures are revealed as complex characters full of contradictions, animated by conflicting wants and needs. They become recognizably human—and, what’s more, recognizably Danish.

As their destinies play out over 24 episodes covering 18 tumultuous years, we watch them struggle with the great issues of the day, from the financial crunch of the depression to the Nazi occupation—along with the attendant changes in social attitudes and mores—as well as the universal and much more private challenges of making ends meet, finding love, finding happiness.

The series concludes with the central character celebrating his having finally gotten everything he ever wanted—at the expense of the happiness of everyone he loves. Not entirely unlike the feeling one might have upon winning a game of Monopoly (the Danish version of which board game is called Matador) by driving the other players—one’s wife and children—out of the game. By crushing them. Yes, congratulations, you won, well played: now perhaps you’ll take a moment to dry your childrens’ tears?

Along the way to the finale, there are births and marriages and deaths, adulterous affairs and unrequited loves, street brawls and social humiliations. We see loyalty and treachery, longing and contempt, ambition and apathy. The whole human pageant is spread out before us, nothing is absent—and no one is spared.

It’s good stuff. You should watch it.

Nørgaard’s creation will endure for decades as something better than a slice of Danish history preserved in amber: it will endure as a collection of Danish lives preserved in amber.