Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen called the election on Wednesday. It will be held on the first of November. The first party leader debate was televised the evening of Frederiksen’s announcement: there were fourteen party leaders on stage. Not all of them were ready for prime-time.

I was unable to watch the full debate, which ran nearly 2½ hours, but was able to see enough to realize that Denmark is almost certainly going to continue its suicidal embrace of green policy regardless of who wins this election.

Just a few hours prior to the debate I’d had an interesting discussion with a stranger, a guy who’d come by the house to pick up some countertops we’d put up for sale online.

As I helped him load the countertops into his car he said he was going to use them for his home recording studio. He was tired of all the ugly metal racks, he said. He described his studio as a kind of sanctuary, the one place where he felt he could let the troubles of the world slip away and just focus on his music. I was sympathetic: I’ve always wanted such a space for my writing.

The “troubles of the world” having been mentioned, we waded into the topic gingerly. As one does.

We agreed on very many things, from big philosophical abstractions down to trivial bits of fluff. We seemed to be kindred spirits.

Time passed swiftly and I found myself wondering whether I had found myself a fine new friend. Had it been a weekend, I might have invited him into the house for coffee or a drink.

And then, in talking about the possible silver linings that might attend the various catastrophes of the forthcoming winter, he conceded that one thing that gave him hope was that it might lead to the end of the monetary system.

Surely I’d misheard him or misunderstood. We were in English at this point: maybe he’d muddled something up in translation?

He seemed to be expecting my agreement, which I was unable to provide.

I probed him with a few delicate questions to try and get him to clarify that he wasn’t talking about the actual end of the actual monetary system, but his answers were indirect and ambiguous.

I said I didn’t think I’d call the collapse of the monetary system a silver lining.

I thought the monetary system had worked out pretty well, I said, warts and all.

He did not entirely agree.

The most generous and charitable interpretation of what he was saying is that he was hoping that this coming winter would bring people around to a recognition that market economies weren’t a good fit for our human needs, and that appropriate changes would consequently be made through normal political processes.

Certainly he wasn’t calling for violent revolution or the establishment of a proletarian dictatorship. Not directly. Nor even indirectly.

I’ve gone over the conversation many times in retrospect, however, and there’s no escaping that his fundamental premise, whether he realized it or not, was that the world was badly organized and needed reordering. To let people be more in touch with themselves, and one another, and our planet.

Not because they themselves have been clamoring to be more in touch with themselves and one another and the planet, but because he thinks they should be.

I’m obviously not going to contradict the assertion that the world is badly organized, but I have to insist on a very important conditional: compared to what?

Compared to any ideal world, sure, it’s a mess. But compared to all the many actual civilizations that have preceded ours, it’s no contest. By any metric, the average human life is better today than at point in human history—we live longer, healthier lives and enjoy more freedoms than any of our ancestors did.

Over the past couple of centuries there’ve been quite a few radical experiments in reordering societies to make them more equitable, more just. Without exception they’ve ended in famine, war, bloodshed, and death on a staggering scale.

All of those experiments were carried out by very smart people who knew exactly the sort of society that would be best for humanity—and were prepared to to anything to bring their utopias to life.

We’re in the midst of one such experiment right now.

Every “crisis” we’re experiencing right now and anticipating this winter is a direct consequence of deliberate government action. The energy crisis, inflation, supply chain problems, shortages, the war in Ukraine: all of them brought to you by government.

More specifically, by leftist governments that have been co-opted by green extremists whose fundamental outlook is that humanity is not the crowning achievement of our planet, but a pestilence upon it.

Their solution to the crises created by government mismanagement is, inevitably, bigger government with even more control over our lives.

Collectivism is once again on the march.

Once again all the very clever people among us have figured it all out and know just how to organize our lives to create a just, equitable, and “sustainable” society. They have only our best interests at heart.

It’s the same old song, but with a sadistic new twist. The collectivism of the past—the stuff that tracks back to Jean-Jacques “Spanky” Rousseau and Karl Marx—was intended to usher in a kingdom of total equality for the benefit of the common man. The hot new collectivism seeks to punish the common man for his crimes against Mother Earth.

20th century communists sought to establish community ownership of everything; 21st century greens seek to annihilate the very principle of ownership:

That’s a screenshot, but here’s a link to the actual tweet.

“It’s 2030. I own nothing, have no privacy, and life has never been better.”

You know who owns nothing and has no privacy?

My dog.

Certainly we care for her and love her, but the price of our care and love is her unconditional submission to our will. We decide where she may and may not go, what she may and may not eat, and when. She can’t even piss or shit without our consent.

She’ll never go hungry in our care, or suffer, or want for anything—but she’ll never know a single day of actual freedom.

That’s the paradise on offer for us now: to be the pets of a ruling class who promise to see that all our needs are met in a manner compatible with the planet’s best interests. We needn’t worry about a thing: they’ll take care of every detail.

(Which assumes they know the best interests of the planet, all our various needs, and how to fulfill them—an obvious impossibility.)

That’s the promise of every major leftist party in the west, and a fair amount of the go-along-to-get-along right. And as Wednesday night’s Danish party leader debate made perfectly clear, it’s the dominant thinking in Denmark all across the political spectrum.

If that’s the kind of thinking my new friend was hoping would be burned away by the crises of the forthcoming winter, I stand squarely on his side. Alas—alas!—I believe it was not the burning away but the actual implementation of this kind of program he was hoping for. Not necessarily in all its particulars, but in its overarching principles: a complete reordering of the world beginning with the principles of property, ownership, and exchange.

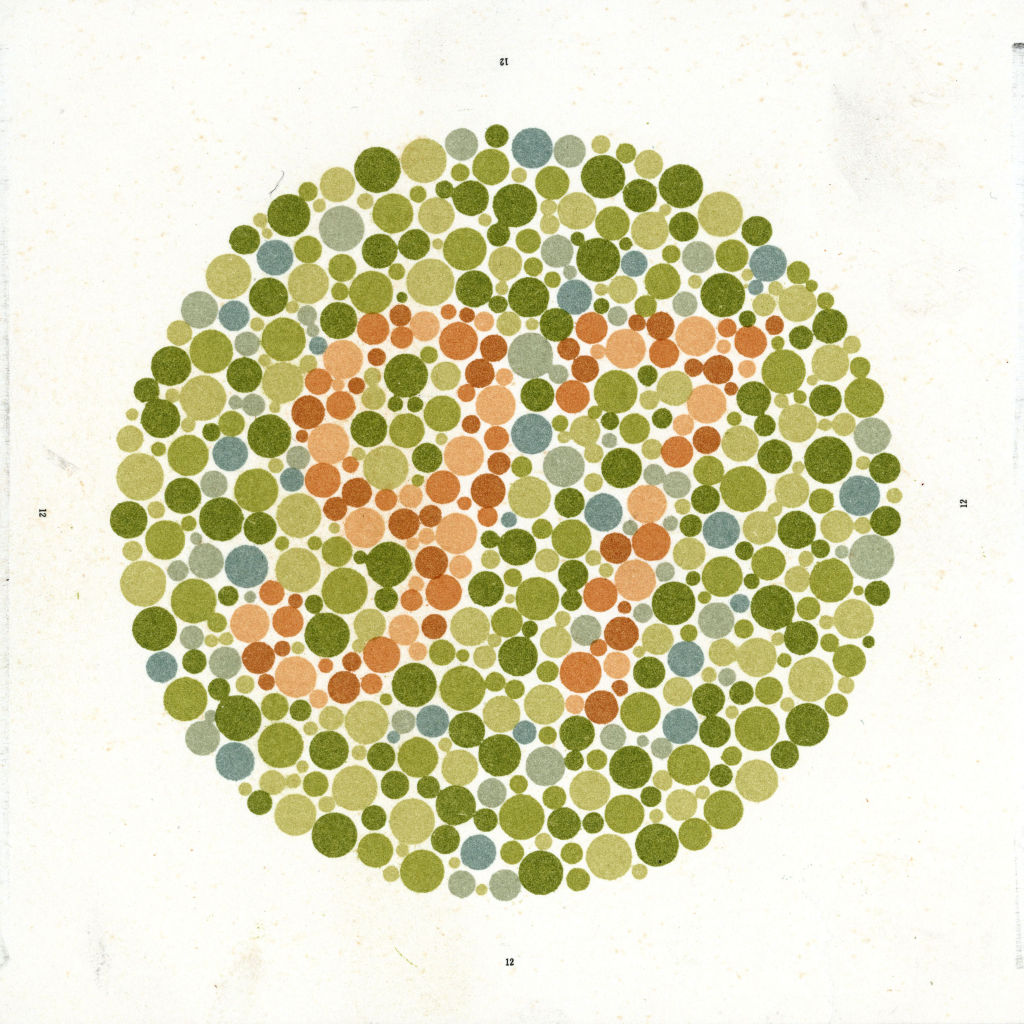

I happen to be part of the roughly 8% of human males who suffer from deuteranopia—a vision disorder that seems to have taken hold of a large swathe of the western public, and a clear majority of our public officials.

Deuteranopia is red-green colorblindness.

In my case, it means that I cannot see anything in the following graphic:

(Because of my deuteranopia I’m unable to say whether or not there really is a pattern in there, but it was one of the images Google coughed up when I searched on “red-green colorblind,” so I’m assuming it’s not just a cruel prank.)

My own colorblindness means I have difficulty distinguishing particular pigments of red and green.

Political deuteranopia means people have difficulty distinguishing between green and red politics.

In A Tramp Abroad, Mark Twain relates the following anecdote:

Mr X. had ordered the dinner, and when the wine came on, he picked up a bottle, glanced at the label, and then turned to the grave, the melancholy, the sepulchral head waiter, and said it was not the sort of wine he had asked for. The head waiter picked up the bottle, cast his undertaker-eye on it, and said—”It is true; I beg pardon.” Then he turned on his subordinate and calmly said, “Bring another label.” At the same time he slid the present label off with his hand and laid it aside; it had been newly put on, its paste was still wet. When the new label came, our French wine being now turned into German wine, according to desire, the head waiter went blandly [about his business]. Mr. X said that he had not known before that there were people honest enough to do this miracle in public…

Our grave and melancholy and sepulchral ruling class has performed just such a miracle on a massive scale with their notion of a collectivist utopia. They have slid off all the labels referring to its Marxist vintage and pasted on new ones advertising its environmental origins.

The contents of the bottle remain the same. It is not wine—not even the “Rhenish vinegar” Twain complained of being served in Germany—but a deadly poison.

If by 2030 we own nothing and have no privacy, we will not be happy.

And we’ll have only ourselves to blame.

The forthcoming Danish and American elections will show whether we’re continuing our deuteranopic slide towards a collectivist dystopia, or whether our vision has cleared enough that we begin to change course.

There’s no cure for actual color-blindness: I’ll never see anything but a blob of dots in images like the one above.

Political deuteranopia can, however, be cured. Maybe not in time for the November elections—but the crises of the forthcoming winter ought to clear a lot of eyes.

That’s a silver lining I could live with.