There’s big piece in Berlingske today on the changed tone of Danish politics.

Something has gone seriously wrong in Danish politics. Now concerned experts are sending a warning to Christiansborg

Tobias Reinwald & Thomas Søgaard Røhde, Berlingske.dk, Sept 4

Only a fraction of this blog’s readers are Danish, so I’m not going to get all deep into the weeds on that relatively long piece. Suffice to say that Danish “experts” are concerned that our politics is becoming increasingly polarized, and that one of the big drivers of that is the nose-diving level of trust between the electorate and their public officials.

This is something we hear a lot these days, and not just in Denmark. As one “expert” notes, for example:

“We have seen the worst horror pictures of what a society with very, very low political trust looks like. We can see that when we look at the USA and France,” says Michael Bang Petersen.

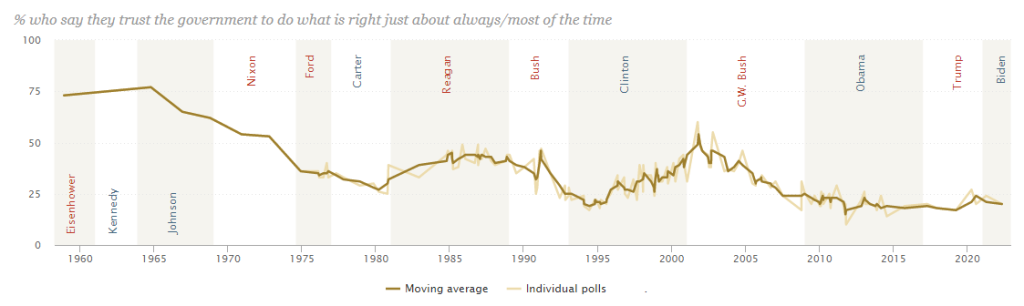

Here‘s a chart from a Pew study that illustrates the “horror picture” of the trend in America:

It’s been half a century since a majority of Americans consistently trusted their government to do the right thing.

(And based on presidential spokesmoppet Karen Jean Pierre having asserted last week that disagreeing with the American majority makes someone an “extremist,” then anyone who trusts the American government to do the right thing is an extremist.)

The Berlingske article is hardly an isolated specimen. Brows are furrowing throughout the western world as earnest and serious people fret over a generalized decline in trust.

There’s a Gallup podcast from about a week ago entitled “What’s Driving Declining U.S. Trust in Institutions?” The host asks his guest, Noah Bookbinder (“president of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington and a former corruption prosecutor”) what’s going on.

So I think we have a couple of different trends that have helped to get us to this point.

Okay.

One is an increasing polarization in American society, so that at really any given time, roughly half of Americans feel like, not only that it’s maybe not their preferred government in charge, but they have a real antipathy to the folks who are in charge.

Doesn’t sound like anything new.

And that has gotten much more pronounced, as you probably know better than I do, over the last 40 years or so.

I think we’re mixing apples and pomegranates here: partisan antipathy has a long and storied history in America. You can hate the other party and still think the government has enough checks and balances built in to ensure that, in Milton Friedman’s words, people can be induced to do the right thing for the wrong reasons.

It seems to me the problem is when the lines between government and party get blurred—or erased.

And then coming out of that, we have, particularly on the right, I think a little bit on the left, but particularly on the right, the rise of kind of populism, which is based on attacking institutions as kind of the basis of appealing to supporters.

It’s always populism with these experts. Always. And it’s always the populism of the right. And because these experts are almost always of the left, they never seem to understand the thing they’re trying to explain.

“Populists” from the right in America and Denmark alike aren’t “attacking” institutions because they hate the institutions themselves, but because they believe those institutions aren’t performing the way they’re supposed to.

I’m not aware of anyone on the left having been accused of “attacking institutions” when they were screaming bloody murder about the Trump administration. (Or either Bush administration, or the Reagan administration. . .) They were understood to be attacking the people running those administrations—for the way they were running them, for the philosophy behind it. No one called them populists, insurrectionists, or a “clear and present danger.” No one bemoaned their lack of trust.

So the people who, the nonpolitical people who work in government going after the courts and all of the sort of institutions that that we rely on.

I don’t know what to make of that sentence, so we’ll skip it.

You know, that is, that’s their bread and butter for attracting support.

So it’s mainly the populism of the right that seeks to attract support by “attacking” institutions. Got it.

And that’s a message that gets out there every day. So that’s one huge thing that’s going on.

I won’t bother with the rest of the podcast, because it only gets worse and reveals an even more blinkered leftist worldview than what I’ve already excerpted (which is really just one long uninterrupted passage).

Also, I don’t want to get mired in America’s particular issues: as I already mentioned, this is a larger western concern right now. An article in the Brussels Times from early July (“Trust in institutions declining across Europe“) offers some findings they find alarming:

Trust in all types of institutions has declined in recent years and is measured on a scale of 1 to 10.

Trust in government fell from 4.7 in 2020 to 3.9 in 2021. It is now at 3.6.

Trust in the news media is at 4.0 in 2022, down 0.2 points from last year and 0.6 points from 2020.

Trust in the EU has fallen to 4.4 after peaking at 4.6 in 2021.

Clearly, trust in government and public institutions is falling.

Instead of looking at the people and wondering why they no longer trust their institutions, maybe we should flip things around so we’re looking through the right end of the telescope: what have western institutions been doing to lose the trust of their people?

I actually will swing back to the Gallup podcast for a second, because that does in fact come up at one point:

HOST: …the public being concerned about particularly what federal institutions are doing isn’t really something new in America. But what is new is our 24-hour constant social media, cable news focus on things when they go wrong. So tell me again, is it really that the institutions’ performance have slipped, or is our focus just much more dramatically expounded on things when they go wrong?

BOOKBINDER: I mean, the answer, not surprisingly, is a little bit complicated. I think, with a couple of exceptions — and they’re important exceptions — but with a couple of exceptions, I think the performance has not gotten worse. You know, there has been corruption and there has been ineptitude in American government since the very, very beginning of American government. And you can point to corruption scandals from the 1790s. And, you know, there are ways in which our government has gotten more transparent, more ethical. You know, administrations like the Bush administration, the Obama administration, the Biden administration have better rules on ethics and conflicts of interest than anything before. And they’ve successively had better rules than the one before them. You know, there are ways in which government is more efficient than it has ever been. and you know, certainly when I worked as a, as a council in the U.S. Senate, I saw there was constant press about all the stupid and awful things happening in Congress and what I saw day in and day out was, you know, primarily really smart, really well-intentioned people working incredibly hard to try to make life better for Americans.

That podcast was recorded one week ago.

If indeed all those “really smart, really well-intentioned people” are working “incredibly hard” to make life better in America, then certainly we’d be fools to trust them, because the one thing most Americans seem to agree on—maybe the only thing—is what a mess their country has become. According to Rasmussen Reports, last week only 29% of Americans thought the country was on the right track.

(They’re obviously all extremists—right, Karen Jean Pierre?)

To get back to my question: when you ask the experts what the institutions have been doing to lose the trust of the people, and their answer is basically “NOTHING! We live in the best of all possible worlds!”, then all we get is one more reason not to trust experts.

I mean, if a woman confided in you that she didn’t trust her husband, would your first question be: what’s wrong with you?

Of course not—unless you happen to know the guy well enough that you either concur with her suspicions or know for a fact that she’s wildly paranoid.

The most natural reply in most cases would be to ask: “Why not?”

In other words, “What has he done to lose your trust?”

Why do our experts consider declining levels of trust in public institutions a problem with the people instead of a problem with the institutions?

Does it not stand to reason that if certain politicians are able to attract voters by “attacking institutions,” it’s because there was already a predisposition among those voters to distrust the institutions—perhaps for good reason?

Our institutions are not entitled to our trust. They have to earn it. And when they fail to do so, it’s not just understandable but necessary, in a self-governing republic, for citizens to let their discontent be heard.

That’s not a new concept. It’s actually enshrined in America’s first amendment—the part people never seem to remember (my emphasis):

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The right to “petition the government for a redress of grievances” is the right to tell the government you think they’ve done wrong and want them to make things right. That’s not the kind of thing you write into a constitution if you expect your government will always do right and deserve the full trust and confidence of the people. It’s exactly what you write into a consititution, however, if you know your government is going to be made up of the most fallible thing on earth: human beings.

The American left used to understand this and even exploit it, by deflecting any criticism of their perpetual protests and outrage with a stupid insistence that “dissent is the highest form of patriotism.”

That’s not true, obviously. Dissent is value-neutral.

It’s subjective. Like trust.

Which brings us full circle: there are good and bad reasons for trusting someone or something, and there are good and bad ways of trying to gain people’s trust.

From where I sit, the governments of the west haven’t done a lot to deserve our trust in recent years.

Far from it.

As exhibit A, I offer only the current state of the western world.

It’s in such a state that there’s no need for exhibit B.

Let’s hear less about how we’re letting down our institutions with our lack of trust, and more about what those institutions are going to do to win it back.

Featured Image: Internet meme.