In a couple of consecutive posts back in the glory days of December 2021 (“Someone Is Blundering” and “No MAGA Country for Smart Men“), I cited excerpts from an Atlantic article by Anne Applebaum. She’s an old school liberal and the Atlantic has become a woke digest, but I thought the article painted a very apt picture of the serious and very real threats our civilizational malaise threatens to unleash upon us.

The article was entitled “The Bad Guys Are Winning,” and it’s still worth a read if you never got around to it back then. I’ll give the same disclaimer I offered in December: “Applebaum’s piece is actually quite good, provided you’re willing to overlook her reflexively partisan interpretations of Trump and Biden, and her willful blindness about the American left’s contributions to many of the problems she cites, even while describing them, but the rest of the long piece is genuinely worth reading.”

I offer all that as context for the journey we’re about to begin.

“The Bad Guys Are Winning,” noted the well-known historian. Now two Danish researchers present a somewhat different conclusion

Thule Ahrenkilde Holm, Berlingske.dk, Mar 28

I’ve never encountered Holm before. He’s apparently on the parliamentary beat at Berlingske, but only got his journalism degree in 2016 and joined Berlingske in 2017. I mention these things not to draw attention to his youth but because I think it’s relevant that his entire career as a journalist has taken place in the garbage journalism world of the Trump-era.

In any case, the “well-known historian” alluded to in the headline is obviously Anne Applebaum. Holm begins by describing her November article:

“If the 20th century was the story of slow, uneven progress towards the victory of liberal democracy over other ideologies—communism, fascism, viral nationalism—the 21st century is so far a story of the opposite,” she wrote several months before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

For although countless politicians and intellectuals have declared in recent weeks that the invasion of February 24, 2022 represents a dividing line, even a cursory glance at the political prose of recent years reveals that for many writers things had already gone to Hell a long time ago.

As Berlingske wrote almost four years ago, after Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the refugee and migrant crisis in 2015, Brexit, and the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in 2016, one could hardly stroll into a well-stocked bookstore without being greeted by titles such as How Democracy Dies, On Tyranny, The Retreat of Western Liberalism and—perhaps most ominously—The End of Europe: Dictators, Demagogues, and the Coming Dark Age.

If you ask the two Danish professors of political science Jørgen Møller and Svend-Erik Skaaning from Aarhus University, however, this dark view on behalf of democracy is distorted.

Holm’s facts are sadly correct here: western leftists really did go into full chicken little mode after the succession of events he mentions, and the titles he lists are real. But as much as I’d love to really tear into all that, we don’t have time to get bogged down in the neurotic literature of the left right now.

Seven myths

Therefore, on March 17, they published the book Seven Myths About Democracy, and among the myths they seek to counter is the claim that democracy is in crisis, has proved ineffective, and is heading for a new interwar period.

To the contrary, “We have not yet, almost regardless of how we look at the numbers, experienced a marked democratic setback,” the authors write in the preface. They continue:

“From a historical perspective, the world has never been more democratic than it is today.”

The professors acknowledge that it’s a tricky business to measure whether democracy is waxing or waning. They explain that there’s a lot of disagreement in this area because there are so many points on which reasonable people can disagree: what is “a democracy?” Do we count democratic countries versus non-democratic countries, or do we compare the number of people living within and without democracy?

The authors base some of their optimism on “the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy,” which “concludes that by the end of 2020, there were 123 democracies and 71 dictatorships in the world.”

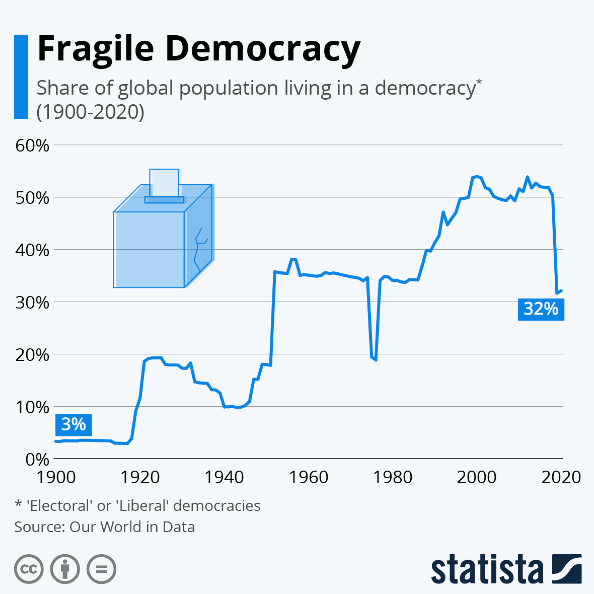

That sounds rosy enough, but here’s a little graphic I found that counts citizens instead of countries:

That’s a hell of a cliff in 2019: the share of the global population living in a democracy dropped from 50% to 32%.

Look at that chart and remember what the professor said: “From a historical perspective, the world has never been more democratic than it is today.”

(In their defense, as I already noted, they acknowledge the problems inherent in trying to quantify something as abstract as democracy.)

Professors Møller and Skaaning offer a rosy perspective that, in some of its broad outlines, I happen to share. A human being given the opportunity to be born into any era in the whole history of our species, but unable to control in what family or country they’d be born into, would be a fool not to choose to be born today. His or her likelihood of starving to death or dying of preventable disease is lower right now than it’s ever been. His or her likelihood of surviving childhood (and her likelihood of surviving childbirth) has never been higher. He or she would have the best chance of not being born into extreme poverty or slavery. And as bad as things are out there, never in human history has a random human being been at less risk of becoming a war casualty.

Those are all wonderful things deserving of our gratitude, and all of them are the consequence of the competitive marketplaces and free exchange of ideas enabled by our democracies.

But the professors didn’t write a book called “Seven Myths About the Quality of Life.”

They wrote a book in defense of the thesis that democracy is not imperiled to the extent claimed by people like Anne Applebaum.

“We can see that the curve is breaking and is on its way down a little, but it is not the case that the world has become almost undemocratic over the past five to ten years,” says Svend-Erik Skaaning.

Much of the debate on the state of democracy is about whether governments in Poland and Hungary, for example, are weakening the division of power or the freedom of the press to ensure informed elections. How apt is that statement to bust the myth of the crisis narrative?

“There you have to take a step back and look at our argument to look at the very core (of democracy),” says the professor. “There is also a reason to look forward to the elections in both Poland and Hungary. Because you have a feeling that the opposition can actually win.”

I have to stop there.

It’s a long article, and the professors say some interesting things (they present a lot of data points that I’ve presented myself in this blog) along with some silly things (Putin and Xi are bad, for example, but not as bad as Hitler and Stalin, so that’s a kind of progress right there!). But what got to me was the constant equivocation—more from Holm than from the professors themselves—of “democracy” and “leftism.”

Democracy isn’t losing in Poland and Hungary: leftism is.

Populist movements throughout the rest of Europe aren’t a threat to democracy, but to leftist hegemony.

Donald Trump was did not jeopardize democracy: he jeopardized leftism.

Here’s another passage (my emphases):

When Berlingske catches Svend-Erik Skaaning over the phone, it seems natural to ask first of all whether the war in Ukraine has repudiated some of the book’s points—or, conversely, even confirmed them?

Svend-Erik Skaaning emphasizes that for both authors it came as a surprise that Vladimir Putin went so far as to invade Ukraine.

“But the interesting thing is that the Ukrainians are offering more resistance than expected. And perhaps part of the will to fight stems precisely from the fact that they are from a democracy rather than a dictatorship. We point out in the book in that historically, all else being equal, there’s a tendency for people who believe in the cause to be able to fight harder than they would otherwise be able to on the basis of the raw number of soldiers and material strength,” he says.

“Another thing that has been seen—and which from a democratic perspective is a pleasant surprise—is the great cohesion that exists in democracies, in the EU and elsewhere.”

Did Putin only dare to invade Ukraine because democracies in the West have shown so much division and insecurity in recent years?

“Yes, it is clearly an interpretation that can be applied, but it then indicates that he has made a mistake in that interpretation. And what else is going on in his head, it can be difficult to figure out,” says Svend-Erik Skaaning.

Skaaning says that people will fight harder in defense of a democracy than they would for a dictatorship. He’s pleasantly surprised by the “great cohesion” the democracies have shown. And although he thinks our civilizational malaise (see Applebaum) is at least partly to blame for Putin’s invasion, this “great cohesion” of ours indicates that he was mistaken to perceive it as a weakness.

Our great cohesion, which is truly great and most admirably cohesive, is on everyone’s lips right now. In recent days I’ve quoted both Mette Frederiksen and Joe Biden bragging about our remarkably unified western unity. But what has it accomplished?

Has it stopped Putin?

Has it saved Ukraine?

I saw or heard news reports today stating that roughly 90% of Mariopol had been destroyed.

Do you think the Mariopolians are thrilled with our unity?

Do you think Vladimir Putin is telling himself “Day-um! I underestimated the cohesion of the democracies! They’re so cohesive!“

The Ukrainian president doesn’t keep running around begging for weapons because Western Cohesion is pushing the Russians out of his country: he wants those weapons because our celebrated unity isn’t doing a goddam thing for his country. He would be justified in paraphrasing Stalin’s famous (and probably apocryphal) epigram, “How many divisions has Cohesion?”

Western democracy is imperiled for the reasons Applebaum spells out very plainly: our lack of civilizational confidence. The professors are only partly right when they point out that citizens will fight harder to defend a democracy than they will to defend a dictatorship: that’s only true if they love their country. And the western democracies, especially America, have fallen into such a filthy froth of self-loathing that just saying out loud that you love your country is enough to get you labeled a dangerous fanatic.

Democracy is an abstraction. No one loves an abstraction. But anyone can love their country, and everyone fortunate enough to have been born free into a democracy ought to love their country.

That we’re being trained not to is the real problem.

“Romans didn’t love Rome because she was great,” Chesterton wrote, “she was great because they loved her.”

And because the people who loved her weren’t driven from polite society by sociopathic malcontents.

One might also point out that ascribing Ukrainian resistance solely to democracy is tap-dancing on rather thin ice. Especially given that there is plenty of historical evidence that Ukrainians (and Russians) have traditionally been quite willing to aggressively defend their homeland, regardless of the nature of their political system.

In fact, it is one of the key characteristics of both countries throughout the 20th Century was that their soldiers were renowned for their tenacity when defending their country, and markedly less effective or motivated when fighting on foreign soil.

Many Ukrainians hated Stalin (for enormously good reasons) and when the Germans attacked the USSR in June 1941, there were many Ukrainians who initially welcomed what they saw as their liberators. However, it quickly dawned on them that the Germans were anything but, and were in fact a mortal threat. So they fought the Germans with incredible ferocity and as soon as the Germans were pushed from Ukrainian soil, some Ukrainians began a new insurgency against the Soviets, which was not finally defeated by Stalin’s forces until 1953.

In that period there was not a shred of democracy in evidence.

So, it may very well be that it is less democracy and more old fashioned nationalism or patriotism that is the key factor, along with cultural traits.

I will also be a lot more impressed by Western “unity” when it moves decisively away from mere words and statements and into actual actions with consequences and real cost to the citizens with the power to un-elect the politicians. So far it is only the Ukrainian people who are feeling the pain.

Out military budgets have been denuded to dangerously low levels and need to be restored. Not in ten years, but immediately. That Mette Frederiksen could get away with a bi-partisan agreement among the major parties that Denmark should reach 2% of GDP spending for defense in 2033 (!) is testament to how unserious the entire political class in Denmark actually is.

Simultaneously, we also need to reorganize our energy production to reduce dependence on Russia. That cannot physically be done simply by expanding solar and wind, despite what the green idiots are saying. So it will be interesting to see what happens when the power really does begin to fail and blackouts become a regular feature.

Maintaining that unity will require reducing the popular spending on welfare goodies, which is the absolutely least favorite discipline of our leaders even under the most favorable circumstances.

Wake me up when they reopen the drilling for oil and gas in the North Sea, when they begin to seriously look at fracking, and when they begin talking about nuclear power again.

What?! Why should popular spending on welfare goodies be reduced? We can just keep printing money! Man, you are really out of touch with modern monetary theory!