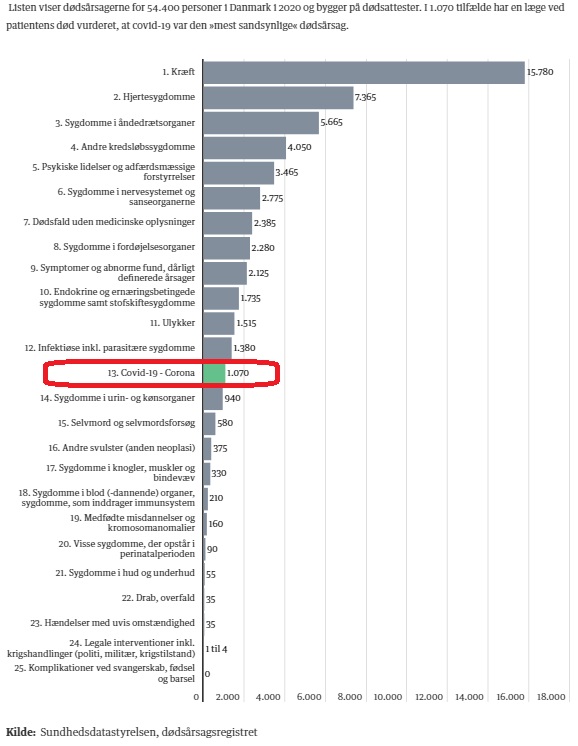

Have a look at this chart (it’s not important if you can’t read the texts):

That’s courtesy of Berlingske, where journliast Philip Sune Dam continues to do yeoman’s work in trying to dig to the heart of Denmark’s actual covid numbers, as distinct from those reported by the government.

What you’re looking at is a chart of the 25 leading causes of death in Denmark in 2020.

The massive gray bar up top is cancer. Just below it is heart disease. And so it goes for another ten causes before we get to covid, which I’ve circled in red.

As Dam is careful to point out in his article (“So many died of covid-19 in 2020—and so many died of other causes“), nobody died of covid in Denmark in the first two months of 2020, while Danes were obviously dying of everything else through all twelve months of the year.

However, even if we annualize the covid numbers, we’re still left with a covid death count of just 1284.

That doesn’t even change covid’s ranking as the 13th most common cause of death in 2020.

I should also note that these deaths are genuinely from covid, not merely with it.

I should also also remind you that the average age of death among 2020 covid victims was in Denmark actually higher than average life expectancy—and that Danish life expectancy actually rose in 2020.

In 2018, when Denmark endured a particularly lethal flu season, 2103 Danes perished from “pneumonia and influenza.” 1882 had died the year before, 1737 died the year after.

All of those numbers dwarf the 2020 covid deaths.

See for yourself in this chart from DanmarksStatistik (“lungebetændelse og influenza“):

Why were we not moving heaven and earth to prevent those influenza deaths? Why did we not even hear about them?

Curiously, the 2020 chart records no deaths at all from pneumonia and influenza.

That’s despite their being responsible for a minimum of at least 50% more deaths in each of the preceding threee years than covid produced in 2020.

Of course, in 2020 there were over 5600 deaths attributed to “respiratory illness.” That category is absent from the 2017-2019 figures.

There were, however, around 3600 deaths per year attributed to “bronchitis and asthma” in 2017-2019; asthma and bronchitis are not listed in the 2020 table but would presumably be included in its “respiratory illness” deaths.

So if we take all those apples and oranges into consideration, we could hypothesize that the asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, and influenza counts from 2017-2019 should all be compared to the “respiratory illness” count in 2020, since they more or less balance out.

In that case, the 1070 deaths from covid 2020 would truly be “excess mortality”—deaths beyond the normal mortality experienced in Denmark.

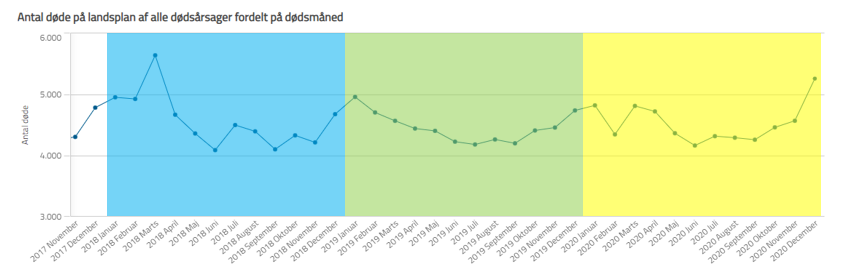

That would be a tidy explanation, except then we bump into this chart:

That’s mortality in Denmark by month, all causes, November 2017 to December 2020.

The colors delineate calendar years, with 2018 in blue, 2019 in green, and 2020 in yellow.

Does 2020 look at all unusual to you?

The peak covid month of December 2020 is notable, but it’s actually lower than the peak influenza month of March 2018.

If those 1070 covid deaths in 2020 were in fact excess mortality—were deaths above and beyond all the other deaths we see in Denmark in an ordinary year—we would expect to see a pronounced difference: a visible “lift” of the 2020 line relative to previous years.

We see no such thing.

The most anomalous feature of 2020 is the radical drop in February, which is ordinarily a high-mortality month. We can assume—cannot prove, but can assume—that in fact February ordinarily has high mortality in Denmark due to seasonal flus, and that this was kept artificially low in 2020 because everyone was freaking out about that weird Chinese virus and taking precautions they ordinarily wouldn’t have.

Which is the reasoning one typically encounters when suggesting that our lack of actual excess mortality suggests that our response may have been a costly overreaction.

“On the contrary,” we’re told, “it illustrates how well our mitigation strategies have worked. Without all that mitigation, our hospitals would have been overtaxed and we would have had many, many more deaths. And had we used these tools against the 2017-2018 flu, we probably would have had many fewer deaths back then.”

It’s a legitimate argument.

But that’s all it is: an argument.

A theory.

We can never actually know, because we’ll never have a control group for comparison.

But we can say that fifteen Danes died of cancer in 2020 for every Dane that died of covid.

That seven Danes died of heart disease in 2020 for every Dane that died of covid.

That more Danes died in accidents than died of covid in 2020.

And at the end of the day, no more Danes died in 2020 than one would have expected to have died based on historical data.

Not only that, but covid preys on the very old and the very ill; seasonal influenza routinely claims the lives of young and otherwise healthy people. Covid may be more contagious and, in the aggregate, more lethal, but the seasonal flu still poses a more serious risk of mortality for the young and healthy.

It still appears to me, based on all the numbers I’ve seen, that the 2017-2018 flu season was much more lethal in Denmark than the current pandemic has been. That was apparent already in 2020, and I wrote about it then, and it’s even more apparent now.

I’m not sanguine about covid. It is—or was—a serious respiratory illness and it took my own father’s life.

However, seasonal influenza is also a serious illness that takes many lives: we’re not going to react with lockdowns, school closings, mandatory masking, and obsessive testing every flu season, are we? We’re not going to mandate flu shots every fall, or develop “influenza passports.”

We haven’t in the past—why not?

It’s worth a moment’s thought, at least.

Economics isn’t merely a financial science: it applies to every sphere of human affairs where there exists, in Thomas Sowell’s phrasing, “the allocation of scarce resources that have alternative uses.”

Simply put: everything’s a trade-off.

For example: every year, about 1.35 million people die in motor vehicle accidents. All of those lives could be saved by eliminating motor vehicles. But doing so would result in death and suffering on an almost unimaginable scale. So we let 1.35 million people die, worldwide, every year, as the price of preventing what would amount to civilizational collapse.

We can’t assess the benefits of our covid mitigation without weighing them against the costs.

The costs include the wrecking of our children’s educations; damage to their mental health (and that of adults); increased alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicides; the bankruptcy of many small businesses; damage to our economy; tangling of our supply-lines; and other effects whose impact may not be discernible for years.

We can’t pretend covid isn’t (or wasn’t) a serious illness; nor can we pretend there haven’t been costs in trying to protect ourselves from it.

I’m not pretending to know what the exact optimal balance of costs and benefits would be for this (or any) pandemic; I don’t think anyone can. I certainly wouldn’t trust anyone who said they could. It’s possible we did everything right, it’s possible we did everything wrong: most likely we got some things right and some things wrong.

My own gut says we got more wrong than right, but only time will tell… and even then, only if we keep digging, and digging, and digging into the numbers so we can at least be better informed the next time we’re confronted with economies of mortality.

That, in turn, could help us save more lives and reduce the collateral damage—so I’m grateful there’s at least one journalist in Denmark taking that seriously.