Let’s start with something very simple: people are not idiots.

There’s an unnamed fallacy that we all understand intuitively. It’s the assumption that people who are smart and competent in one thing are smart and competent in others, and that people who are stupid or incompetent in one area are clueless in general. The strength of this generalization is inversely proportionate to how much we know about the individual in question.

Seated next to a nuclear physicist at a social event, we’re likely to believe anything she tells us about nuclear physics, no matter how hare-brained, simply because we know so little about the subject ourselves. We will also then listen attentively to her opinions on politics, economics, and goat herding out of deference to the great knowledge we attribute to her in an area we don’t understand ourselves.

And when someone tells us something that we know to be false, or demonstrates incompetence at some task we consider, rightly or wrongly, to be quite simple, we’re going to dismiss their ideas about everything else, and their abilities in all other fields, as suspect.

The people we know best are tangles of brilliance and idiocy, competence and cluelessness: they can do many things we can’t, but also can’t do many of the things we can. We make allowances for those we know. But strangers like that idiot behind the cash register that just made three mistakes in two minutes? A hopeless moron, period. Even though, for all we know, she’s just distracted because she was up all night working on her doctoral thesis on the gravitational impact of dark matter.

This isn’t Michael Crichton’s Gell-Mann Amnesia effect, which I’ve written about elsewhere, but something much more universal about the way we judge one another’s competencies. It isn’t even necessarily conscious: it seems instinctive. Our judgment leaps from the particular to the general with startling immediacy, and the less we know about someone (and the less we know about their particular area of competence or incompetence) the more we extrapolate from whatever little piece of them we do know.

That’s a human reality we have to live with. It’s not going to change. I’ll call it the Bloomberg Fallacy for reasons I’ll get to later. Meanwhile, hold that thought.

America was founded as a self-governing republic. The radicalism of the idea that mere citizens could somehow organize themselves into a functioning polity is hard to overstate: that a bunch of farmers and shop-keepers could populate and run an entire nation with nothing more than a rulebook to guide them was almost impossible to believe.

That idea succeeded not because it was radical but because it was right. Of course people can govern themselves. Every family on earth, every household, is a kind of tiny nation with its own budgets and policies, factions and fault-lines, allies and enemies, and internal power struggles galore. You don’t have to read Bastiat or Friedman to understand economy; you don’t have to read Clausewitz or Sun Tzu to understand the importance of defense; and Plato isn’t required to recognize the need to address injustice. Anyone who’s raised a child knows that the human capacity for debate requires no foundational studies in rhetoric.

In short, any human being raised by and among other human beings is capable of serving as the kind of citizen required for a self-governing republic.

Which is why I began with the proposition that people are not idiots.

That in itself is apparently a radical proposition to a lot of people these days, as the reactions to Brexit and the election of Donald Trump illustrated back in 2016.

Brexit became law, and Donald Trump became president, because the self-governing republics of the U.K. and the U.S. chose, by their own rules, to make them so. And our sages said, “These events are birds of a feather: our people have become too stupid for self-government. Democracy is in crisis.” And they swiftly set to work to try and undo what the people had done.

When the self-governing peoples of a free republic make a collective decision by the means allowed for it in their little rule book, they are doing exactly what they’re supposed to be doing. That doesn’t mean such decisions are always for the best, but self-governing republics are a lot like teenagers that way: sometimes they can only learn from the consequences of their own decisions.

Curiously, no one I’m aware of said, “The reactions to these events are birds of a feather: there are many among us who no longer believe in the idea of self-government. Democracy is in crisis.”

And yet that observation, unlike that of our sages, is actually supported by the facts: you cannot prove that people are too stupid for self-government, but your saying that they are is irrefutable proof that you reject self-governance. (Saying “the people will be ready to manage their own affairs only when they’ve been properly educated” doesn’t mitigate your contempt: it’s just a dangerous first step down the road to authoritarianism.)

It’s the Bloomberg Fallacy writ large.

The “inflection point” events of 2016 did not represent “a populist uprising doing crazy and stupid things across the western world,” even though that’s how our celebrated sages have been trying to represent it.

The more important revelation from 2016 was that our wealthiest and most powerful citizens had determined that the rest of us were incapable of governing ourselves; or, more specifically, that they no longer felt a need to hide that belief.

The notion that people have become too stupid to govern themselves is a radical proposition. And unlike the radicalism of the second half of the 18th century, which lit the torch of liberty in America and France, this radical proposition was, and remains, wrong.

And if 2016 was the inflection point that made this tendency widely apparent, 2020 appears to be the year in which it’s gone mainstream.

The western world is now divided between two competing ideas, neither of which is new.

The first was perhaps best articulated by Abraham Lincoln seven score and seventeen years ago this month on a field in Pennsylvania: “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The second has been articulated in many ways by many people since the dawn of civilization, but is perhaps most succinctly expressed in the words of an unknown seventeenth century medical doctor: “faciamus experimentum in anima vili.” Which means: let’s perform an experiment on the wretched soul.

It is the mantra of all the social scientists, politicians, philosophers, theologians, pundits, and bartenders who know the answers to all the questions and are simply baffled at our unwillingness to get in line and do as we’re told.

The gulf between the followers of these two ideas has widened this year because our experts and sages have revealed the limitations of their wisdom just when we needed it most. It has also revealed their contempt for the very people they claim to be trying to help.

I’m trying to avoid links and citations in this piece, but I want to make room for some comments Mike Bloomberg made back in 2016 (emphasis mine):

The agrarian society lasted three thousand years and we could teach processes. I could teach anybody, even people in this room, no offense intended, to be a farmer. It’s a process. You dig a hole, you put a seed in, you put dirt on top, add water, up comes the corn. You could learn that. Then we had 300 years of the industrial society. You put the piece of metal on the lathe, you turn the crank in the direction of the arrow and you can have a job. And we created a lot of jobs. At one point, 98 percent of the world worked in agriculture, now it’s 2 percent in the United States.

Now comes the information economy and the information economy is fundamentally different because it’s built around replacing people with technology and the skill sets that you have to learn are how to think and analyze, and that is a whole degree level different. You have to have a different skill set, you have to have a lot more gray matter. It’s not clear the teachers can teach or the students can learn, and so the challenge of society of finding jobs for these people, who we can take care of giving them a roof over their head and a meal in their stomach and a cell phone and a car and that sort of thing. But the thing that is the most important, that will stop them from setting up a guillotine someday, is the dignity of a job.

Note that he’s not merely saying a lot of people will need to transition to a new economy, or need to learn new skills to find employment in same, both of which are pretty obviously true. In saying “you have to have a lot more gray matter” he’s saying you have to have a bigger brain than that paltry little clump of cells between your ears. You have to know how to think! How to analyze! In saying “it’s not clear the teachers can teach or the students can learn,” he’s saying that this informationally-oriented world of the future is simply beyond the reach of many people. There’s no ambiguity here: he’s saying we could house and feed these morons easily enough, but we need to find them jobs so they still have a sense of dignity. Not because they deserve dignity, mind you, but because otherwise they’ll be setting up guillotines to take their frustrations out on the good wise people… like Michael Bloomberg.

We need to find them jobs, because they’re too stupid to navigate their way through this brilliant world that we enlightened geniuses are building for them. Also, if we don’t find them jobs they’ll end up killing us.

Spoken like a true man of the people.

This is the same man, by the way, who as mayor of New York City led wars on salt (too much sodium!) and the size of soft drinks served and sold around the city (too many sugary calories!). This is a man who genuinely believes he and his peers need to build guard rails all over society to prevent idiots like you and me from hurting ourselves.

Of course, Mr. Bloomberg requires no such guard rails himself. According to a 2009 article in the New York Times, Mr. Bloomberg “sprinkles so much salt on his morning bagel ‘that it’s like a pretzel,’ said the manager at Viand, a Greek diner near Mr. Bloomberg’s Upper East Side town house.” But that’s okay because he’s smart, not dumb like you, and therefore knows how much salt he can handle.

Mr. Bloomberg doesn’t seem to recognize that if you’re building a world that can’t accommodate everyone, the problem isn’t with the people but with your world.

The idea that we’re wretched souls who need to be saved from ourselves by our betters is neither unique nor new. (Take a bow, Jean-Jacques “Spanky” Rousseau.) It’s also an idea that should be rejected categorically by anyone who gives a damn about liberty—as it usually is when the choice is presented honestly. And that’s why it’s almost never presented honestly.

In any case, this is why I think the “Bloomberg Fallacy” is an apt name for the mistaken idea that people who are clever and competent in one area, as Mr. Bloomberg clearly is in finance and tech, are also clever and competent in others (such as governance); and that people who are incompetent in one area (business and tech) are probably clueless about everything else, as Mr. Bloomberg seems to feel about those teachers and students.

Do you think Mr. Bloomberg believes that people who are too stupid to work in tech or manage their own salt and soda consumption have what it takes to govern themselves?

There’s a great deal of uncertainty in the western world right now, more than there’s been at any point in the past half century. (In 1968-69 the lethal Honk Kong flu was sweeping the world, the Vietnam war was raging, the Cold War was running hot, and domestic American politics were even more riotous and violent than they are today.) Today’s uncertainties boil down to this one essential question: are the people of the self-governing republics of the west going to be permitted to continue governing themselves, or will we submit ourselves to the yoke of an aristocracy of sneering Bloombergs?

What we see with the reactions to the pandemic, and the reactions to the reactions to the pandemic, and with the American election, and reactions and counter-reactions to the election, and with the reactions and counter-reactions to the economic consequences of the pandemic, and with all the associated questions arising from this convergence of events, are simply our civilizational struggle over this essential question.

I know which answer I prefer: that government by and of and for the people shall not perish from the earth. It is not the answer preferred by our sages, by Big Tech and the establishment media and the international left. But I am honest about the nature of the question and I am unambiguous in my answer.

Those on the other side are not.

Big Tech wants to control the exchange of information to protect you because they believe you’re too stupid to process ideas on your own.

The establishment media are blocking some stories and fabricating others to protect you from ideas they believe may harm you and win your support for ideas they believe will improve you, because they believe that they know your interests better than you do.

The international left wants more and more control of society to emanate out from an ever-larger government because they sincerely believe an enlightened class of benevolent bureaucrats can manage everything better than we wretched souls can on our own.

Michael Bloomberg loves you: he only wants to reduce your access to salt so you stupid peasants stop giving yourselves heart attacks. Also he wants to give you some stupid make-work job to keep you busy so you have “dignity” and don’t come for his head when you realize his beautiful new world has no place for you.

Almost all the dysfunction of 2020 is rooted in our inability to have a simple and direct conversation about something fundamental to our civilization: are we or are we not free people fit to govern ourselves? To ask the question is to answer it, and that’s exactly why the enemies of self-government are working so hard to deny the question itself.

It doesn’t matter which way the American election goes, or how the pandemic plays out from here. What matters is who gets to decide: the people, or the mandarins who despise them. And that’s not a choice we’re being allowed to make, because the mandarins are in control of pretty much everything and don’t like to have their authority questioned. For our own good, mind you: remember, they’re only trying (so selflesslessly!) to save us from ourselves.

They’ve inverted the question from how much we’re willing to trust them to how much they’re willing to trust us.

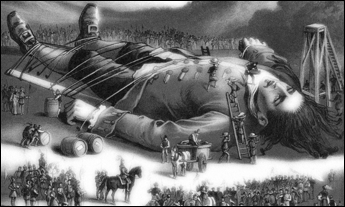

Think of Gulliver tied down by the Lilliputians: it’s not a bad metaphor for the million little Bloombergs doing their best to tie down the free-born citizens of democratic republics. Let that big guy run around unfettered and god knows what kind of damage he’d do to himself and the rest of us!

And when I say it’s not a bad metaphor, I mean it’s exactly the metaphor Swift intended.

How much credibility does the World Health Organization deserve after having told us there was no human-to-human transmission of the Wuhan Virus… and that, by the way, it’s racist to use the geographic naming convention we’ve been using for centuries? How much credibility do our healthcare experts deserve after flip-flopping so many times on the value of masks, of fresh air and sunshine, of Vitamin D? For insisting that protests against lockdowns were a clear and present danger to the national health, while protests in support of the (Marxist) Black Lives Matter movement were not? How much credibility do the newest climate models deserve, when all previous models have been wrong? How much credibility do the establishment media and their pollsters deserve when they’ve been so spectacularly wrong about the past two American elections? When they stand in front of burning buildings and assure us that protests have been mostly peaceful? How much credibility do mathematicians deserve when they subvert mathematics to partisan politics? How much credibility does Joe Biden deserve when he repeatedly insists that the whole reason he ran for president was something provably false?

“Nobody’s perfect” is a perfectly legitimate excuse for well-meaning people who’ve made bookkeeping errors or changed lanes without signaling or put pineapple slices on a perfectly innocent pizza. It doesn’t cut it in when you’re insisting on the right to control human lives based on your expertise.

Self-governance requires universal trust, but that trust must be earned rather than demanded. People are not idiots, and when their trust is violated there’s a price to be paid. That price comes in the form of skepticism, cynicism, and contempt. When trust is not earned but demanded and skepticism is attacked rather than answered, things get messy.

We’ll get through the pandemic. America will get through its transition of power. Those are minor things.

The erosion of trust in our sages and the contempt of those sages for the people they’re supposed to be serving are not minor things. They are big things, enormous, and if left unchecked they will indeed lead to Mr. Bloomberg’s guillotines.

Experts and specialists and elected officials are tolerable and useful when they’re trusted and when we feel they’re genuinely attuned to our best interests.

Take away the trust, take away the faith in their benevolence, however, and all you’ve got left is tyranny.

And people won’t endure it for long because people are not idiots.